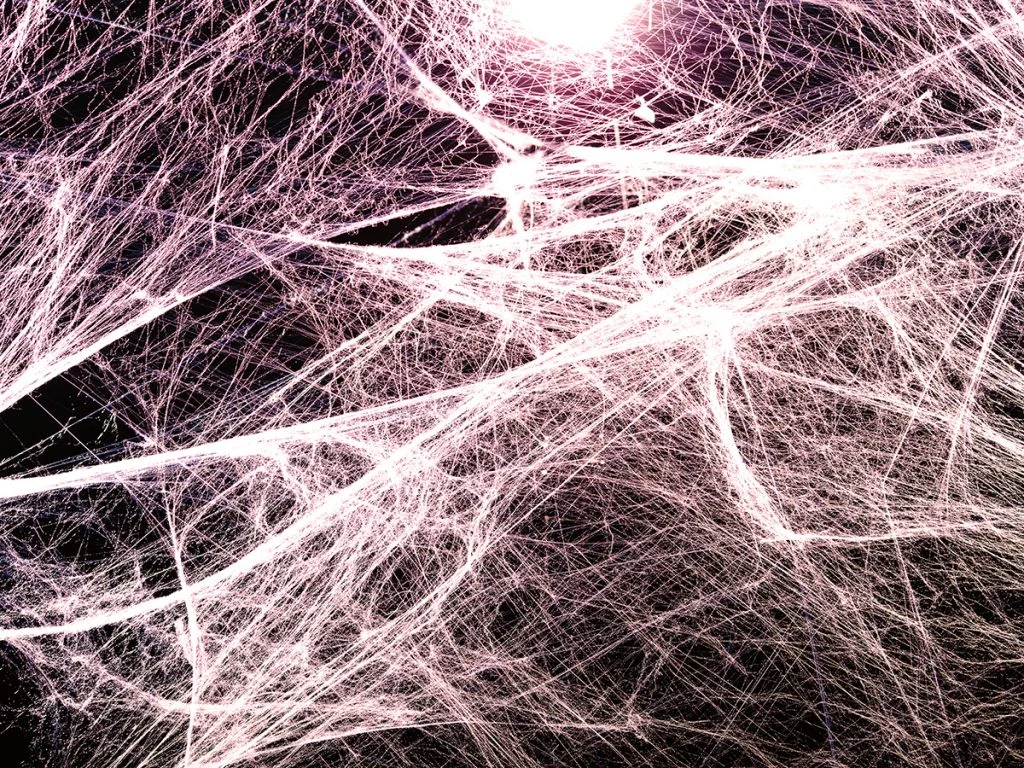

I feel like “fascia” has rapidly become a buzzword and frankly it totally deserves it. It’s pretty amazing stuff and it connects all parts of our body. Fascia is a thin membrane that wraps muscles, nerves, arteries, organs, bones — virtually everything. Wherever you look in the body fascia is there. Earlier in medical history when doing cadaver dissections, anatomists used to cut it out of the way to get to the stuff they were looking for, a specific muscle, an organ, a bone. Part of this lack of knowledge of fascia could be the reason western anatomy has a tendency to compartmentalized and keep things separate. Now that fascia itself is under the microscope its showing connections to all parts of the body. In some cases these connections are very similar to the pathways of the acupuncture channels laid out 2000 years ago in the Ling Shu, one of the oldest medical texts in human history and the foundation of the medicine we practice here at BAP. It just may be that fascia plays an integral part in the way Chinese Medicine works and why we acupuncturists do the things we do.

There’s a lot of data that’s being transmitted through fascia, its like if you had a taut suspension cable, tap one end and the vibration will travel to the other. Every time a force is applied to the body it is transmitted through this web to be processed. Where the fascia is and it’s thickness determines what it is referred to. For example “retinaculum” is used to describe the fascia of the wrist and is involved in the dreaded carpal tunnel syndrome, or “aponeurotic” tissue which can be found over the low back and is associated with that achy back pain of yours. It’s all ways of classifying the fascia. It’s in these tissues where a lot of free nerve endings exist that are constantly monitoring the body, where, for example, the wrist is in relation to the elbow. How one muscle is contracting so its opposing muscle can relax in order for things to move smoothly.

Fascia helps your body know where it is in space, something known as proprioception. Think of it like a big net full of GPS sensors sending data to the brain so it can calibrate where all your limbs are in relation to each other. This allows complex movements that we take for granted such as picking up a glass of water to drink or opening a door. A lot of this information is gathered in dense accumulations of fascia. Most of these accumulations occur around the joints, where the limbs come together with the trunk, the low back, down the center of the chest and abdomen, and the back of the neck. When you think about it, it’s often where we acupuncturists place our needles. There’s even fascia that entangles our organs and holds them in place by suspending them from the spine. So if you ever hear a practitioner say they’re treating your internal conditions via your back, there’s a theory that this is how that works.

In order for fascia to communicate effectively across the body this tissue has to be smooth and free. If not the result will often be pain and poor range of motion. Often if you take someone in pain and examine the fascia it looks clumped up and knotted, it could even throw off the body’s sense of where things are and in turn affect how you move. Think about those little GPS sensors, if they’re not in their right place they will send the brain distorted information. A “knot” in one area can in turn affect distant parts of the body. Take the clothes you’re wearing as an example: find a spot and twist a knot in it, that knot pulls the fabric from every corner of the garment. This can happen in the body, too, when the fascia in one area is tight and clumped together, it’ll pull on the regions its connected too, in some cases far away. It’s why if you come in with low back pain I may end up sticking needles in your legs and feet. Wherever the problem is, the back say, everything that connects to it can be affected, such as the lower limbs.

This is why Chinese Medicine can be so effective. It has been studying these lines (we refer to them as channels or meridians) for generations. Seeing how they all connect and work together. Even when you look at someone doing the exercise known as Qi Gong, which can be used in Chinese medicine as physical therapy, all the movements involve the whole body. There’s an appreciation for everything being connected. Nothing is ever isolated to just one muscle. This is a reason why your practitioner may put needles far from the area in pain, not just locally where it hurts.

I was trained to combine Tui Na (Chinese Medical Massage) and Acupuncture to treat pain and discomfort. Through bodywork and touch, one can get a sense of the fascia and how it reacts, by physically moving and manipulating it, it’ll begin to relax and smooth out. In Chinese medicine, we refer to this as opening the channels to allow the free flow of Qi and Blood. The acupuncture then continues this treatment allowing the body to relax into it and return to a neutral state. This allows for the body to move freely and without pain and discomfort, as all the channels of communication are now open and free. It’s pretty amazing to read these ancient texts describing where the acupuncture channels go, how they’re described as starting in the foot, knotting around the knee, going up the leg and into the back etc. Then reading modern anatomy texts on fascia and seeing the same trajectories but with more detail and photos to show it. To me, it’s the same thing, a progression of the same concept that started 2000 years ago and keeps getting more and more detailed as we look closer at the body. For more information I’d recommend looking up Carla Stecco, author of Functional Atlas of the Human Fascial System, or Dr. Helene Langevin who studies acupuncture and its connection to fascia.